NGO security – learning from experience. Tales from the Field

Ever since Steve Dennis sued the Norwegian Refugee Council over its handling of the kidnapping of four NRC staff from the Dadaab camp in northern Kenya, the security of NGO workers has become high priority. Dennis, who was kidnapped in 2012, won the case in 2015. One NGO worker tells us how, even on the most straightforward assignment, things can easily go wrong.

It was April 2003 and I was on my first trip to Somaliland, the former British protectorate that became part of the greater state of Somalia in 1960. After a civil war with the east of the country and the collapse of Siad Barre’s government in 1991 the region broke away from the Republic of Somalia and became the self-declared Republic of Somaliland.

I arrived in the capital Hargeisa, late morning, where I met my driver, Ibrahim (not his real name). My destination was Sheikh, a small town set in a mountain range, three hours drive from Hargeisa, where I was due to spend three nights. It was, I was told, a scenic route. Ibrahim took me for a quick lunch at a nearby hotel, from where we were to set off early afternoon to reach Sheikh before dark.

During lunch Ibrahim got a call on his mobile phone to ask us to wait for another passenger – a member of the board of the international NGO I was working for – who was coming in from Dubai. His flight was due at about 2.30 so we could still make Sheikh before the light faded. At the same time Ibrahim was asked to buy some extra supplies.

So Ibrahim and I headed back to the airport to await the flight. Hargeisa is not a big airport and immigration procedures are usually quick. However, the customs formalities for this person took longer than expected, and were then followed by afternoon prayers.

So it was about 3.30 when the man appeared, at which point he told us that he had decided to stay the night in Hargeisa and would not be going to Sheikh after all. He used Ibrahim's mobile phone, and then decided to keep it for the duration of his stay. Neither of us challenged him – he was our senior, it was my first meeting with him and I could not have foreseen what lay ahead.

It was now 3.45, and by the time Ibrahim had bought the extra supplies it was 4.30 when we were finally ready to leave.

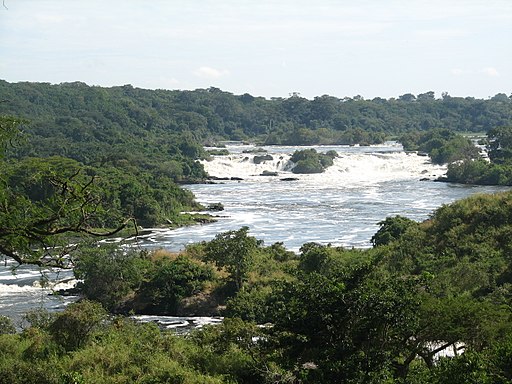

About 30 minutes out of Hargeisa we had to cross a river bed, which is easy when it’s not raining. But we were in the middle of the rainy season and the river had flooded during the short afternoon rain. So we joined the queue of cars waiting for the water to subside. At first I wandered down to the water, checking on the level, enjoying this unscheduled stop, but after a while I got bored and stayed in the car chatting to Ibrahim. The light began to fade but I wasn’t overly worried. Ibrahim knew the route well and seemed a good driver.

It was well after 6.00 pm when we finally braved the river bed. We made it across and one by one we left the other cars behind as they turned off the main road. And then we saw a lorry, followed shortly after by another, and another – each one announced by its undimmed headlights as it raced towards us. Ibrahim said they were on their way to collect consignments of khat, the narcotic leaf that is popular in Somalia.

The lorries were travelling fast, each one keen to be first at the collection point, where they would load the best leaves and return overnight to sell their produce the following day. Suddenly I was jittery, scared of the speed at which each lorry approached us and I remember yelling when I thought we were about to have a head on collision. But Ibrahim knew the road and the car and seemed bemused by my fears.

After about an hour of travelling we turned onto a mountain road. Sheikh is a high altitude town and getting there involves some steep and windy roads. Doing it in the dark was not exactly as planned, but we had no choice. I looked forward to reaching our destination. Not having a phone we hadn't been able to tell our hosts about our delay and I knew they would be worried.

Suddenly, half way up the hill, Ibrahim stopped and a man appeared from nowhere with a small live antelope in his arms. The two had a conversation I didn’t understand and then Ibrahim told me that he was going to put the animal on the back seat and take it home with him. It seems he had arranged this rendezvous in advance, but had not expected to be late.

At this point I'd had enough. We were already late, it was dark and we were driving uphill in the middle of Somaliland. I put my foot down, asserting that we were going nowhere with an animal in the car. Knowing that he was pushing the limits Ibrahim didn’t argue. I’m embarrassed to say that I didn’t even ask what he was going to do with it. My mind was solely focused on reaching our destination - which we did sometime later, much to the relief of my hosts.

Six months after that journey two elderly British teachers were murdered in Sheikh and in April 2004 a car carrying staff working for the German aid organisation GTZ, was attacked as it crossed Somaliland. A Kenyan woman and a Somali colleague were killed and a German passenger seriously injured. Since then, all international organisations have had to operate under strict security guidelines, including being accompanied by Special Police Unit armed guards in and between towns.

My journey was a walk in the park compared to that one, but it did make me realise that I always travelled without any form of briefing, relying on information from co-workers and trusting that the system would work. Not long after, I decided to write briefings for every country that fell within the office remit, including information about airports, weather, currency and culture. I felt the cultural aspect was especially important, bearing in mind that we travelled in countries far more conservative than Kenya, where we were based. Women in particular needed to know how to dress for certain regions and how to interact with local people. It may seem obvious now, but those were different times.

That Somaliland trip, along with the subsequent tragic events described above, was a wake up call for me and after that I insisted on special insurance for working visits to places that might be considered conflict zones, and not covered by my own medical policy.

I also took home some valuable lessons: safety, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder, and my eye became much more discerning, so that even when a place appeared to be safe I never took it for granted. And I learnt to listen to, and obey my instincts - when something doesn’t feel right, it usually isn’t.

.jpg)

Travel Jember Surabaya Says:

June 27, 2022 at 03:49pm

nice info